Then & Now: What Fashion Has Gained & Lost

Inside the Archive: What Older Luxury Reveals Up Close

Luxury is supposed to be obvious the second you touch it: the weight of the hardware, the smell and softness of the leather, the way a seam sits flat and clean, the fact that the piece looks better after years of wear instead of worse. But lately, luxury has started to feel… weirdly hollow. Prices are climbing, logos are louder, and yet the materials and construction don’t always match what you’re paying for.

My question isn’t whether luxury is expensive; it’s whether it’s still well-made. If luxury is priced like it’s “forever,” why does so much of it feel built for “right now”? Has craftsmanship changed, or has our definition of value shifted alongside it?

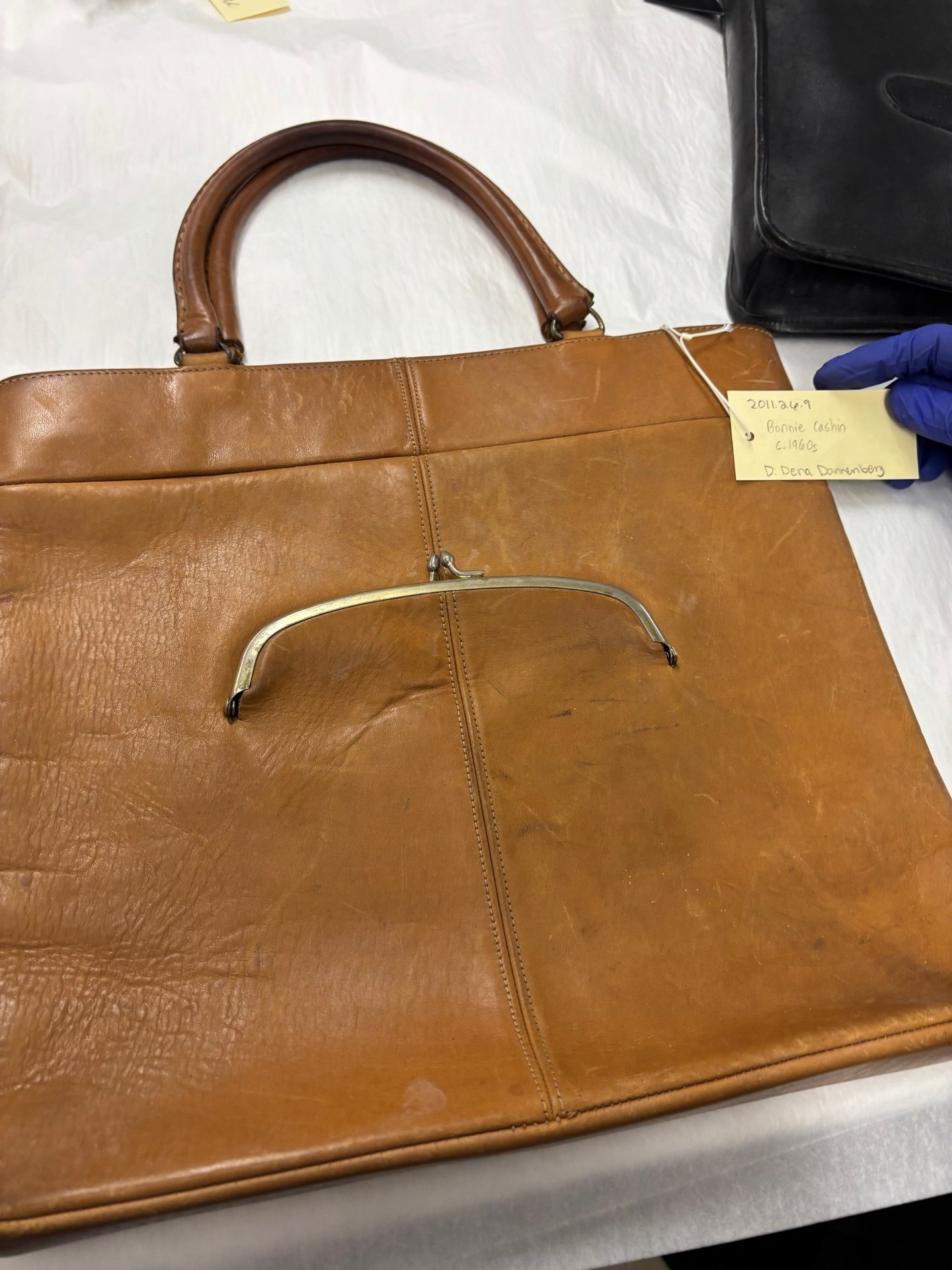

To figure that out, I delved into the collection with Monica Stevens Smyth, the manager of the Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection, a design historian who, quite literally, inspects clothing as a lifelong pursuit. We pulled vintage shoes and bags from shelves and flipped them over like mechanics inspecting engines. We focused on what can’t be faked: materials, construction, durability, and repairability.

Quality used to be part of the price. It’s evident in stitching density, whether hardware is set or glued, turned edges versus edge paint, and leather that develops a patina versus coated surfaces that crack. But over the last century, fashion has shifted from small-scale craftsmanship to global production, from exclusivity rooted in scarcity to value rooted in experience and image. That structural change matters because when scale increases, shortcuts often follow.

“Good Aging” vs. “Bad Aging”

“So how do you tell patina from damage?” I ask, holding up a worn leather sole. Monica doesn’t hesitate. “Damage is typically inconsistent and localized,” she explains. “Patina is a more uniform aging process.” She points to the toe of a leather sole where the fibers are compacted and darkened. “You see pins here?” she says. “It’s just a thicker, more durable material.” The leather hasn’t peeled. It hasn’t split. It’s compressed. It’s adapted.

Good aging softens. It deepens. It reacts chemically over time. On leather, she explains, “Patina is the supple softening that comes with age.” Bad aging, on the other hand, exposes shortcuts. “Nowadays you have really thin... one-millimeter thin layers just glued.” Thin coatings crack. Bonded leather scrapes. Edge paint peels. The glue dries out. “That’s degrading,” Monica states, “When you start to get thinner parts and spots, the holes. That’s structural damage.” Patina happens within the material.

Degradation happens on top of it, or worse, beneath it. Once you see the difference between material transforming and material failing, it becomes impossible to ignore. And that leads to the next question. If aging reveals the material, construction reveals the labor.

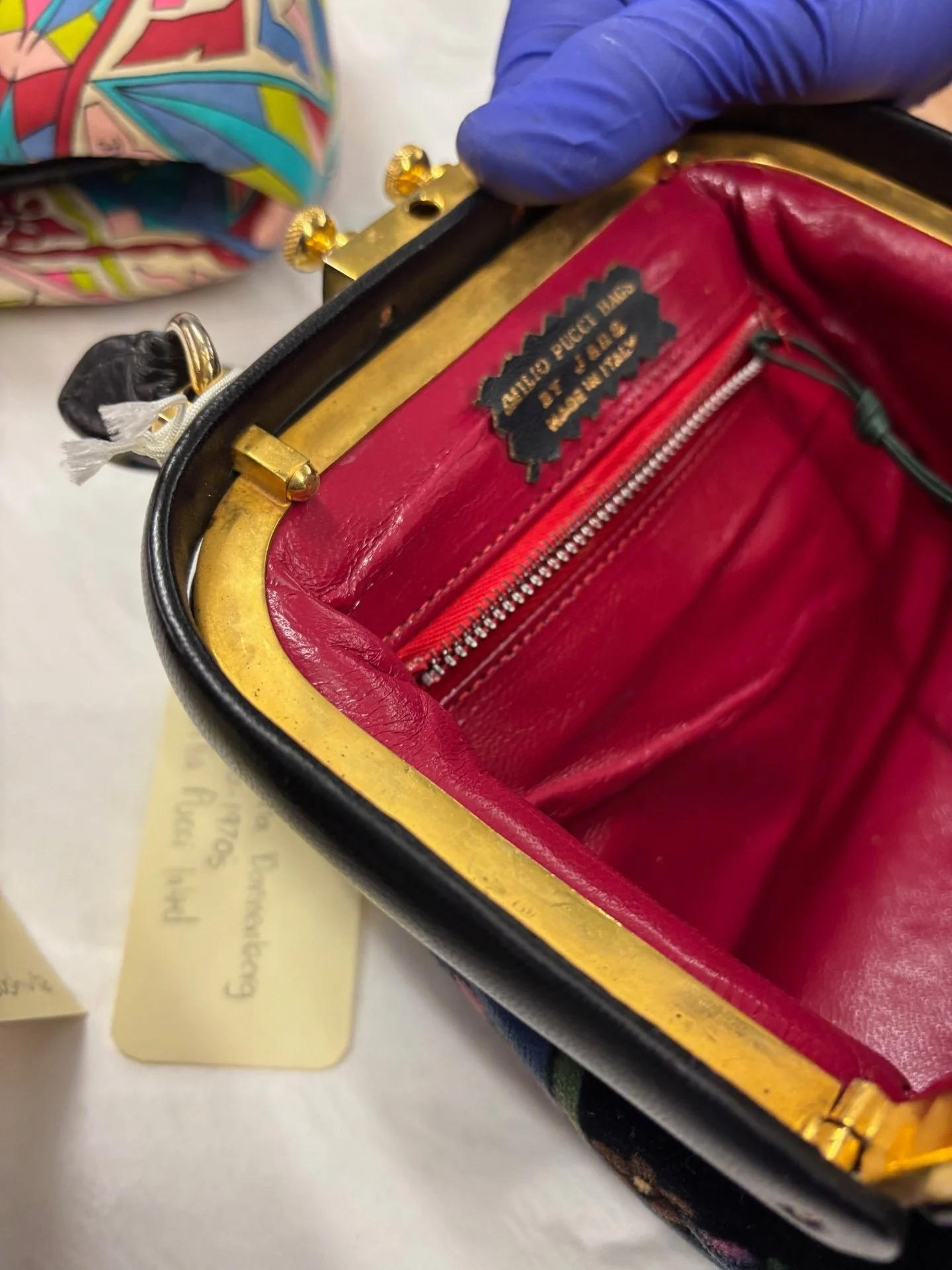

Labor You Can Literally See

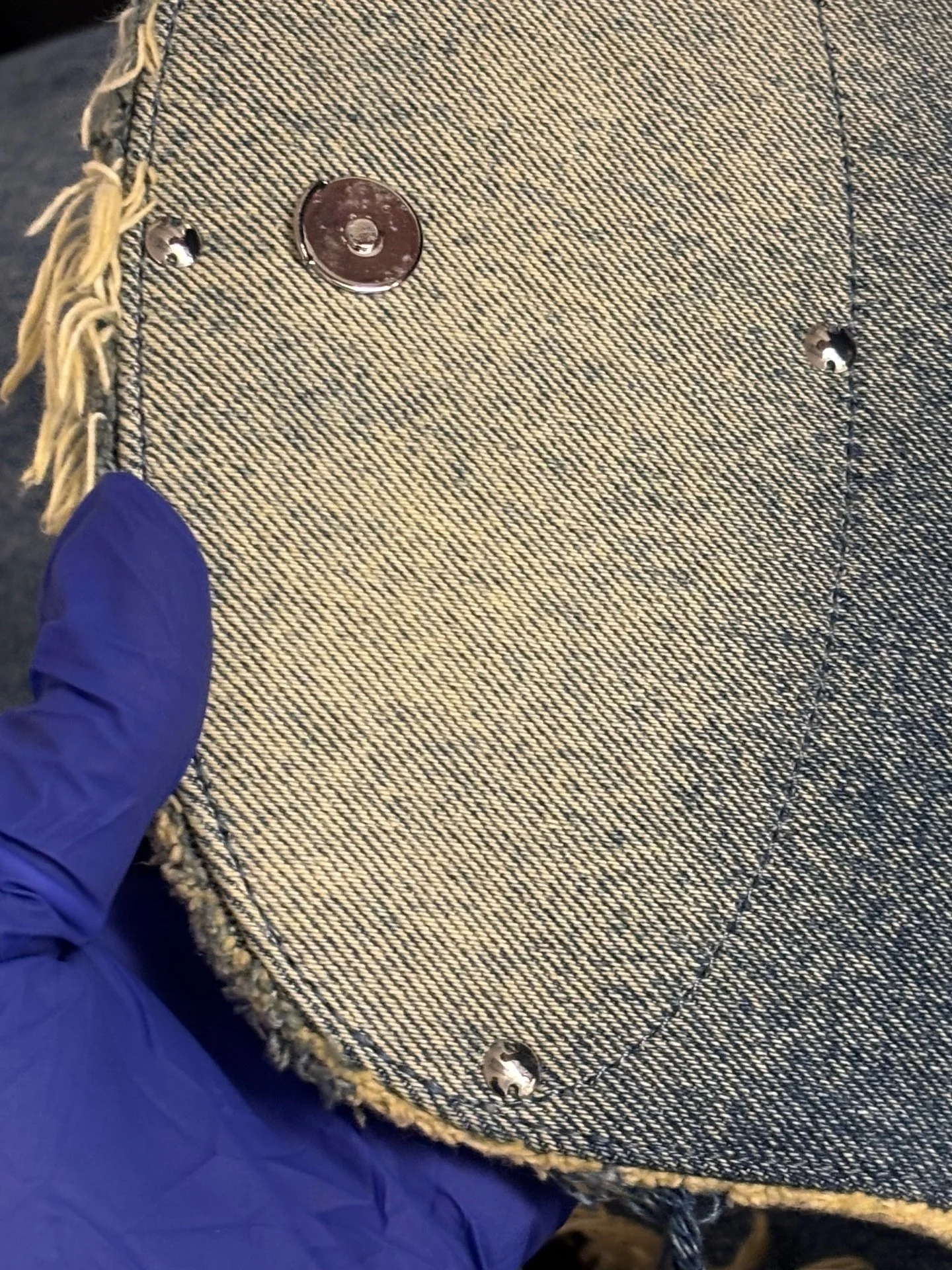

“Where can you physically see time in this piece?” I ask. Monica flips over a shoe. “Nails versus glue,” she notes, succinctly. In older pieces, “they were nailed in, not glued.” If something needed reinforcement, they used more material. “Now they’re... trying to use as minimal material as possible.” “They’re like screwed in, though,” I observe. “Yeah, they are,” she replies. Designed to prevent premature wear, repairable, adjustable, and intentional. That’s labor. You see it in stitching density. In hardware, it is secured with screws rather than adhesive. In turned edges, folded and stitched rather than painted shut.

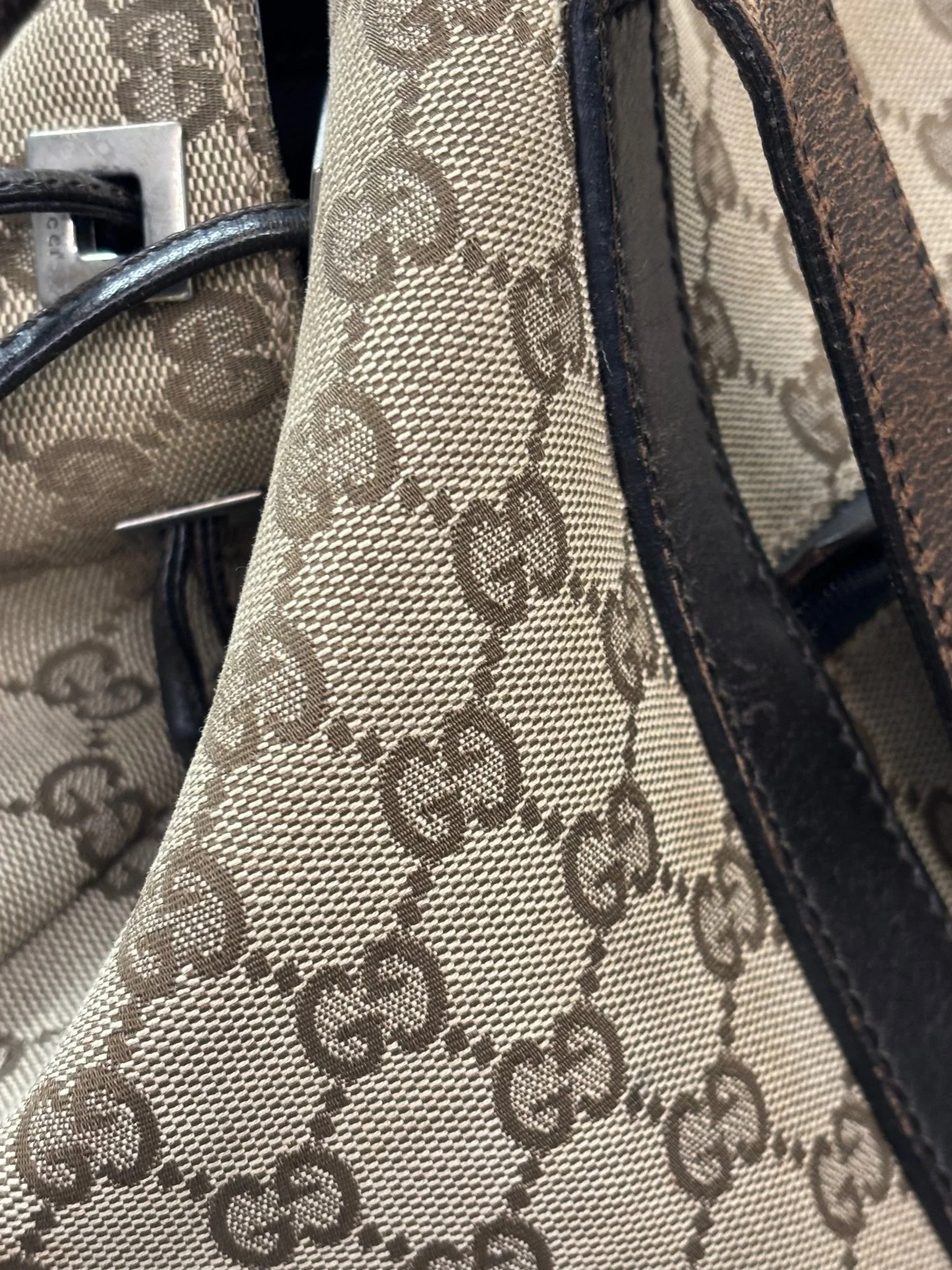

“When scale increases,” She states flatly, “shortcuts follow.” You can see it in thin veneers, plastic zippers, and hardware plating that rubs off. Even in authentication, the signs are physical. “Authentic leather has a natural, non-symmetrical grain,” I noted. Repeating patterns means stamping. Blurry logos mean corners were cut. Labor hides under flaps. Inside the seams. Beneath hardware plates. And when it disappears, the object feels lighter, even if the price gets heavier, which brings us to the part that makes people uncomfortable. Because sometimes, what you’re paying for isn’t weight. It’s narrative.

The “Buying Air” Problem

To illustrate this, I chose tiny luxury bags that can’t even fit a phone. “$2,600 for a miniature,” Monica says, eyebrows raised. Does it require miniature precision? Or more labor? Is it the same material as a practical size? The modern market often prioritizes brand perception over build quality. Nylon bags are priced alongside leather. Logos are amplified. Hardware is hollow.

“You’re buying people... service... even the packaging,” she offers, point-blank. That’s part of luxury now, too: the experience, the box, and the story. But when thin layers are glued instead of nailed, when coatings crack instead of patinating, when interiors feel lighter than the exterior branding suggests, the price starts drifting away from the material. Luxury, as she explains, has shifted from material integrity to symbolic value. It’s not that craftsmanship no longer exists. It’s that branding has gotten louder than construction. And that shift is visible. So, I asked her the question that’s been sitting between us all afternoon.

Modern Luxury: Higher Prices, Lower Material Honesty

“If you were to buy a luxury bag today,” I asked, “who would you buy it from?” She pauses. “Probably resale,” she says, because older pieces were built differently. Heavier materials. Less conservative usage. More nails, fewer glue shortcuts.

Luxury used to be defined by material integrity, the kind you could see in reinforced seams, full-grain leather, and pieces built to be repaired. Today, it’s more often defined by branding, experience, and cultural relevance. Fashion has gained accessibility and global visibility, but it has lost a consistent commitment to material honesty, and real luxury still comes down to what stands the test of time, not what photographs well.