Life Through a Wabi-Sabi Lens

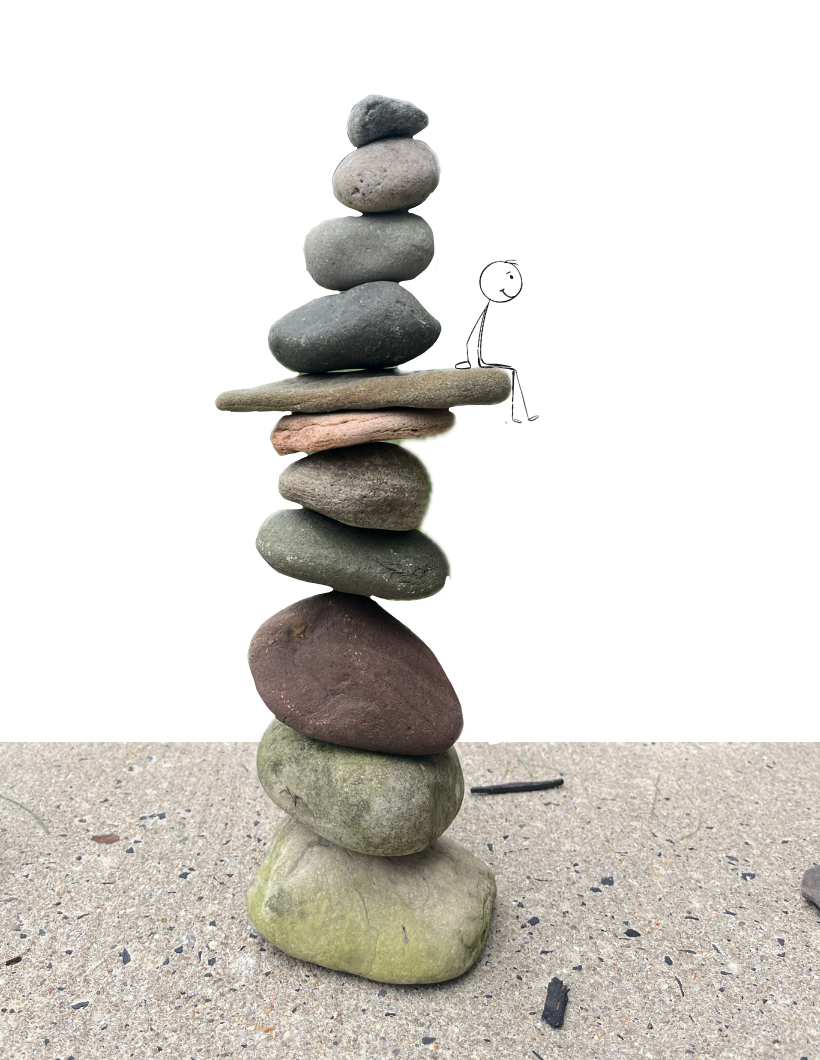

This summer, I got into making rock cairns in my front yard, meticulously balancing rocks and seeing how high I could stack them before they toppled over. I liked to sit outside and eat my breakfast anyway, and there were plenty of rocks surrounding me – it felt like an invitation to play around. People in my neighborhood started recognizing me, passing by on their morning walks: “Back at it again?” Some even asked to take pictures.

One day, my neighbor curiously pulled up in front of my house.

“What’re you doing?”

“Stackin’ rocks.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know, it’s fun.”

She laughs.

I know stacking rocks seems like a silly activity; why spend so much time doing it when they’re just going to fall over? My rock cairns would always eventually be blown over by the wind or run down by the lawn mower, but that gave me the opportunity to start over! I realized that stacking rocks was teaching me serenity – bringing my attention to what I was doing and living fully in the present moment. Art doesn’t have to be complete, or permanent, or perfect to be worthwhile. Neither does anything else really.

I didn’t learn to see life through a wabi-sabi lens by studying a thick book on Japanese philosophy. I learned it by spending hours stacking rocks, making wobbly bowls on a pottery wheel, and falling off my bike in the middle of the street on a summer afternoon. I learned it through listening to other people’s stories, and how they stay grounded when things don’t go as planned.

Most people make perfection their be-all end-all goal – but perfection is exhausting and honestly, boring. Real life is uncertain. Real passions leave fingerprints. Real stories scar.

That’s where wabi-sabi appears.

Wabi-sabi, a Japanese philosophy, asks us to slow down and see the beauty in all things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. It has been passed down by word of mouth for generations and can be described as the antithesis of our Western notion of beauty, which defines it as something perfect and enduring. It serves as a reminder that nothing – not art, not bodies, not moments – is meant to last forever.

It is quiet and simple and human. In a culture suffocated by the pressures of peak performance, curated feeds, and polished everything, wabi-sabi feels like a deep exhale.

When I started pottery classes earlier this year, I was obsessed with the symmetry, the uniformity, and the perfection of the pottery wheel. I was mesmerized by videos of potters consistently pulling even walls of clay, their hands steady, their pieces symmetrical and smooth, as if balance were second nature to them. I convinced myself I could get there if I just tried hard enough, expecting it would take a month, maybe? Instead, the harder I tried, the worse I seemed to get. I was overthinking it. If one thing went wrong, the piece was scrapped. I wanted perfect mugs, but I got lopsided blobs instead.

At first, I thought, “Psh, I’ll never make hand-built pottery,” silently judging, “It looks like a child made it.” But slowly, I realized that the marks, and fingerprints, and uniqueness of ceramics were what I loved the most. When I started, my goal was to produce uniform and perfect pieces; I thought that was what people would be most impressed by. But now, I’d rather every piece look different. Instead of feeling failure, I’ve started to feel ownership. A part of me is in my piece. It doesn’t look like anyone else’s work – it looks like mine.

Paul Yanuzzi, a fellow potter and science enthusiast, shared his perspective with me when I told him this story: “Production is just production. You can make a million of the same plates. And it’s just that. It's production stuff. So I think you would’ve gotten tired of it anyway. You make mugs, but each one's a little different. So I think people develop their own styles, and for you and the wheel, I mean, it takes time to really develop that.”

Leigh Roeger, who has been doing pottery at our studio for a few years now, says, “When I first started doing pottery, I actually would throw things that didn’t come out right. I would say, ‘I don't belong here. This isn’t for me.’ Everything made me mad. Everything was stupid.”

Plenty of times, I’ve seen Leigh giggling at a piece that came out wonky; I asked her how she got to this point from where she started, “Well, I always tell people, ‘don’t get attached to your pieces’. If it breaks, I say ‘Eh, I can always make another one’.” This outlook can take a while to obtain, but when you do, “you’ll free yourself of a lot of disappointment”.

She enjoys creating pottery in a community studio, and sometimes that's the most essential part. Art is creating, not finishing. Let the creative process be a reward enough in itself. Detach yourself from obsessing over the outcome.

Appreciating and accepting the way things are is essential to living a fulfilling life.

This summer, I fell off my bike in the middle of the street on the way to get a sandwich. When I got home, I saw myself in the mirror – chin scraped, shoulder skinned, and knees purple. After weeks of healing, I’m left with a big scar on my shoulder. A lot of people ask me if it’s a burn, and some people may consider it unfortunate, but to me, it’s a story. Proof that I lived, that I fell, that I healed. Instead of hiding the scar, I like to think of it as a permanent reminder of the adventure I once had. If you think of bodies as works of art – scars, birthmarks, or anything else, are the wabi-sabi of the body. They can be called “imperfections”, but that doesn’t mean they’re not beautiful. But wabi-sabi can apply to so many more things in life than rocks, ceramics, and scars.

A friend of mine, Paige McFadden, studies culinary arts at Drexel. I knew how much she loves baking, and I was curious to hear her take on wabi-sabi in the kitchen. Even though baking requires precision, Paige genuinely loves the process, success or failure.

She shares, “I'm remembering some of my birthday cakes. At the end of the day, I kind of just have to tell myself sometimes to shut up, it's okay. I can't get this swirl to be perfect, or this line is crooked, or it's not completely symmetrical, but, like, isn't that the joy of it all?” Baking kept her going through hard times, and it was most rewarding for her to share it with others and make them smile.

“Presentation is important, because you eat with your eyes first, but I would never want my plate to look prettier and taste worse. But I think that is so joyous, just feeding people and bringing them happiness.” Her mindset is honest and inspiring, “It can be relaxing, it’s push and pull. It’s kind of like with any art, it’s okay not to be perfect. And I feel like lots of artists struggle with that. You just want it done, and you want it done a certain way. And if it doesn't look like the certain way that you think it should be done, then it's awful.”

When I spoke with Paul some more, I learned that his life has wabi-sabi written all over it. He likes to build things of all sorts and understands the frustrations that accompany that, especially with pottery, “Let imperfection be what it is. It doesn't have to be perfect. I mean, I think you see that in some of my work where I just let it go. And that attests for this. Because that's another thing with pottery, it can break. But even when you're creating, it can alter into something different. Maybe you didn't have in mind, but that's okay.”

Paul’s interest in science led him to study holograms for a long time. Holograms use lasers to record light from all directions to develop an image, similar to film, but on glass. Now retired, his passion for them remains the same, and you can tell that just by the way he talks about it. “One of the beauties of the hologram, when I first got into it, was if I take a holographic image of you, and I smash it into a million pieces, and I put it back in the light in the right way, that tiniest piece will have the entire image of you. So when I put them all together, then I see Susannah from here, and I see her from here, and that's what gives us steps of perception.”

The broken hologram perfectly reflects the essence of wabi-sabi. Even when broken, beauty can be seen from the right angle.

If you still feel like wabi-sabi is something you can’t yet live by, take it from Paul, at 66 years old, “You never stop growing. We all want our life to turn out the way we think it’s gonna be. But then life brings you different things. And sometimes it’s the most beautiful things in the world. If you overthink it, it sometimes interrupts the beauty of the creation.”

If your mind has gone mad, try stacking some rocks.

If you need to learn to detach, try pottery.

If you have scars, be proud of the story they tell.

Let imperfection, impermanence, and incompletion lead your way to a wabi-sabi life.