Beyond Expectations: Redefining Asian Success in Creativity

My Story — Finding My Way Back to Creativity

Some of my earliest memories are of sitting on the floor with crayons scattered around me, filling pages with color until my hands were completely smudged. Art was my favorite escape as a child, and I spent hours drawing, painting, and entering school art competitions. Even then, creativity came naturally to me, and so did curiosity. I loved science just as much. By the time I was ten, I was proudly telling everyone that I wanted to be a doctor.

As I grew older, that confidence began to fade. Somewhere between the practical expectations around me and my growing love for design, I started to question what I truly wanted. In my teens, I imagined a future in creative fields like architecture or fashion. Still, because my parents saw how much I enjoyed science, they gently encouraged me to pursue a career in medicine. My mom would always remind me that with medicine, you cannot go wrong. Wanting to make the safer choice, I selected all science subjects for my A-levels and eventually accepted a place in medical school.

It did not take long for me to realize that I did not belong there. Between endless studying and lengthy lectures, I felt myself growing increasingly disconnected from who I was. Imposter syndrome grew heavier each day until I finally decided to leave after my first year. Returning home to Sri Lanka was terrifying because I had no clear plan, only the certainty that medicine was not where I was meant to be. A few months later, I landed an internship with a local fashion designer as her social media marketing intern, and that experience changed everything. Working in a creative environment where ideas became visuals and visuals became real impact reminded me of who I had always been. My parents saw how happy I was, and for the first time, they understood that this was where I belonged.

When I began looking at universities abroad, I focused on programs that connected creativity with real-world industry experience. That search led me to Drexel’s Fashion Industry and Merchandising program. Reading through the curriculum felt strangely familiar, as if my interests were reflected back at me. Since then, making the Dean’s List throughout my freshman year has reassured me that I am finally on the right path.

Coming from Sri Lanka, where creative careers are often seen as unstable or treated as hobbies rather than real professions, I have made it essential to keep my culture at the heart of everything I create. The blue lotus, our national flower, has taught me the power of symbolism and memory. It reminds me of my grandfather and represents resilience and calm, qualities that helped me through the uncertainty of leaving medicine behind. The lotus became a recurring motif in my design work, and in my final project for Design III, I challenged myself to create a massive lotus sculpture. It became more than an assignment. It became a reminder of my growth, my roots, and my choice to return to creativity on my own terms.

Rashidah Salam, Design Professor, Malaysia

“Without art and design, humankind loses a way to heal—and a way to remember who we are.”

Malaysian-born artist and educator Rashidah Salam has spent her life turning problem-solving into a form of art. Growing up in a village where craft was a part of everyday life, creativity was never something she had to look for. It surrounded her in the hands of her neighbors and elders, who made things with care and intention. She learned by watching them work step by step, a method that mirrors the way she now guides her own students. Unlike many Asian households, where children often feel pressure to follow traditional career paths, Salam’s family never placed those expectations on her. They cared about stability but never defined what it needed to look like. That freedom shaped her relationship with art from the very beginning.

Even with an undiagnosed reading difficulty that made long texts hard to get through, she discovered a strong ability to observe, interpret, and understand information quickly. That way of learning eventually led her back to art after completing her A-levels and exploring more conventional subjects. She later received a government scholarship to pursue a master’s degree in Studio Art and eventually played a role in building Borneo’s first university, before making Philadelphia her home.

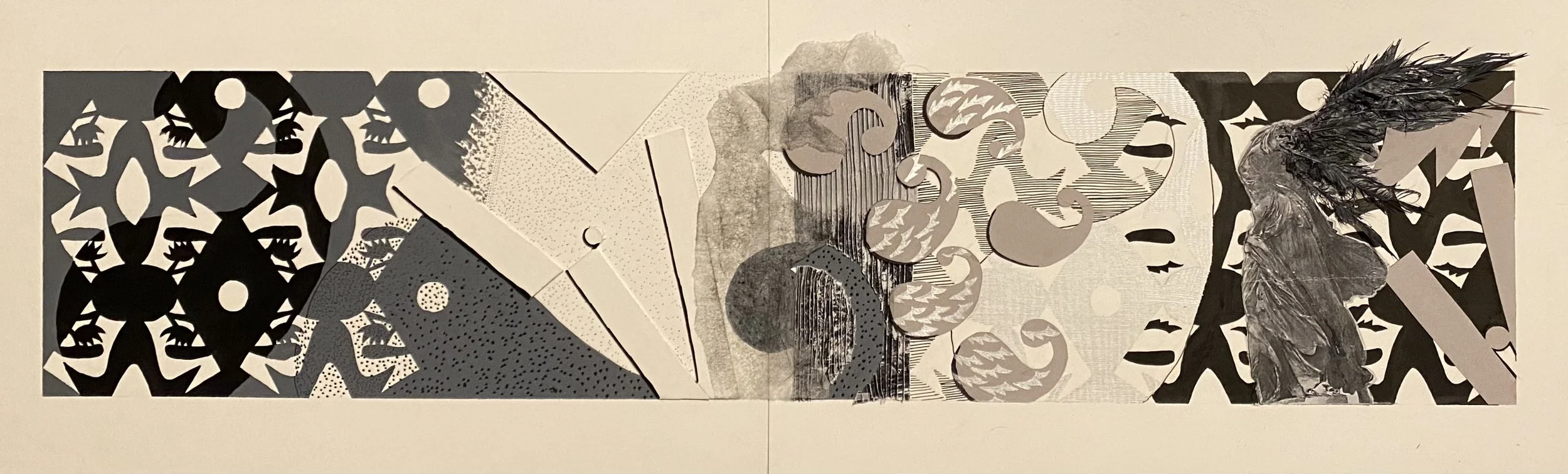

In the classroom at Drexel, Salam treats her students like a community. She sets high standards and emphasizes process, precision, and thoughtful craftsmanship. Her Malaysian craft sensibility shows up in everything she teaches: patience, discipline, and the belief that meaningful work cannot be rushed. She does not make dramatic statements about culture; she expresses it quietly through her everyday life, whether she is wearing her traditional baju or weaving bougainvillea-inspired forms into her creative projects.

Even though Salam did not face the cultural pressure that many Asian creatives experience, she understands it deeply through her students. She sees how often they question whether art is enough and offers them a message that blends respect with steady confidence. Honor your elders, but let the quality of your work speak for your path. For her, success is not a destination but a long journey shaped by perseverance through homesickness, cold winters, and the constant rhythm of deadlines. She holds a simple belief about art and legacy: if we do not protect our own traditions, someone else will, and they will claim the story.

Zeba Farida, Graphic Design Student, Bangladesh

“Graphic design isn’t the easy path people think it is. It’s where I get to prove the value of creativity every single day.”

Growing up in Dhaka, Zeba Farida spent her childhood recreating projects from YouTube craft videos, building miniature worlds out of paper, tape, and whatever she could find. She was equally strong in science and, like many South Asian students, kept one foot in each world. For her A-levels, she took physics, chemistry, math, and art, keeping her creative interests alive while still pursuing a practical academic path. Architecture seemed like the middle ground everyone could agree on. It felt creative, respectable, and familiar to her parents. Until a last-minute visa restriction unexpectedly forced her to choose her second-choice major, Graphic Design.

What happened next was not a moment of conflict, but a careful family conversation. Her parents spent time going through the program with her, reading about courses in motion design, animation, coding, and design strategy. They realized graphic design was far broader and more flexible than they had imagined. In a family where many women had paused their careers after marriage, the idea of working from anywhere mattered. Graphic design offered that possibility, and with that understanding, they fully supported her choice.

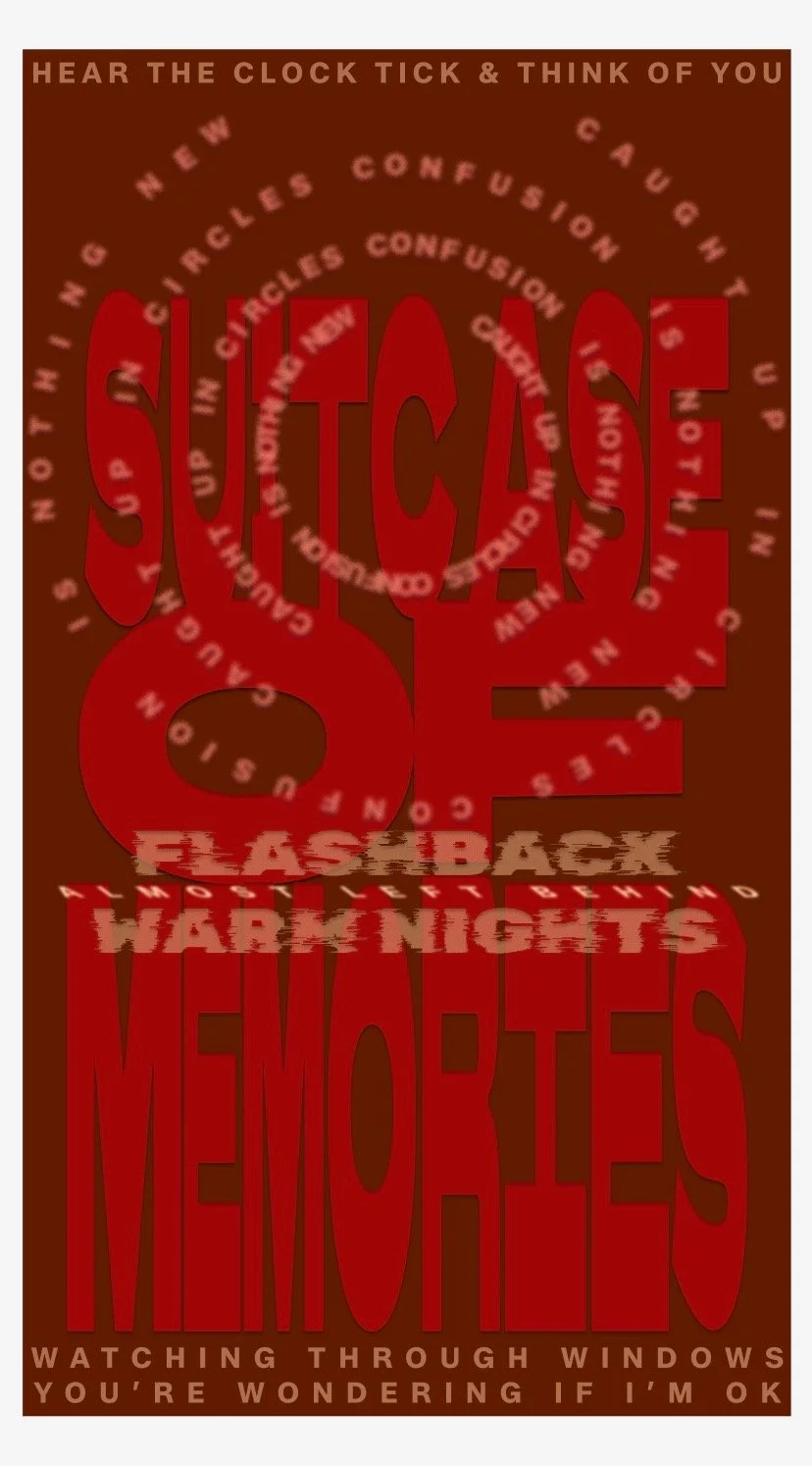

In Westphal, Farida found a collaborative community that treats design as serious work rather than simple decoration. Even so, she sometimes feels the quiet pressure to prove the value of her field, especially when friends in STEM assume her assignments are easy. She lets her work answer those assumptions. Her process is intentional and research-based, shaped by South Asian visual language: the delicate lines of henna, the curves of paisley, and the symmetry of traditional motifs. She uses these elements not as surface decoration but as authorship, reclaiming designs often borrowed from South Asian culture without acknowledgment. She hopes that brands will reference, not appropriate, the visual language of her heritage.

For Farida, success is not measured by prestige or salary. It is measured by the freedom to keep creating in every stage of her life, whether she is in Philadelphia or back home in Dhaka. As she puts it, she wants to keep doing the work and not stop for anyone or anything.

Preksha Wade, Fashion Design Student, India

“Success, to me, means doing work that’s honest and true — not just what gets attention.”

For Preksha Wade, creativity was never a sudden discovery. It had always been present in her life. She grew up in Bengaluru surrounded by drawing, painting, sculpture, music, and theatre. When her father’s job took her family to Wisconsin and later to California, she continued exploring those same creative interests in new environments. She eventually returned to India for high school, and it was during those years, especially in the quiet of quarantine, that she began to understand how fashion could become a form of storytelling. She realized that what we wear is one of the ways we present our personal narratives to the world.

When she told her parents she wanted to pursue fashion design, they fully supported her. As the eldest daughter and the first in her family to study abroad, she chose Drexel for its resources, its co-op program, and the independence it offered her to think deeply and experiment freely.

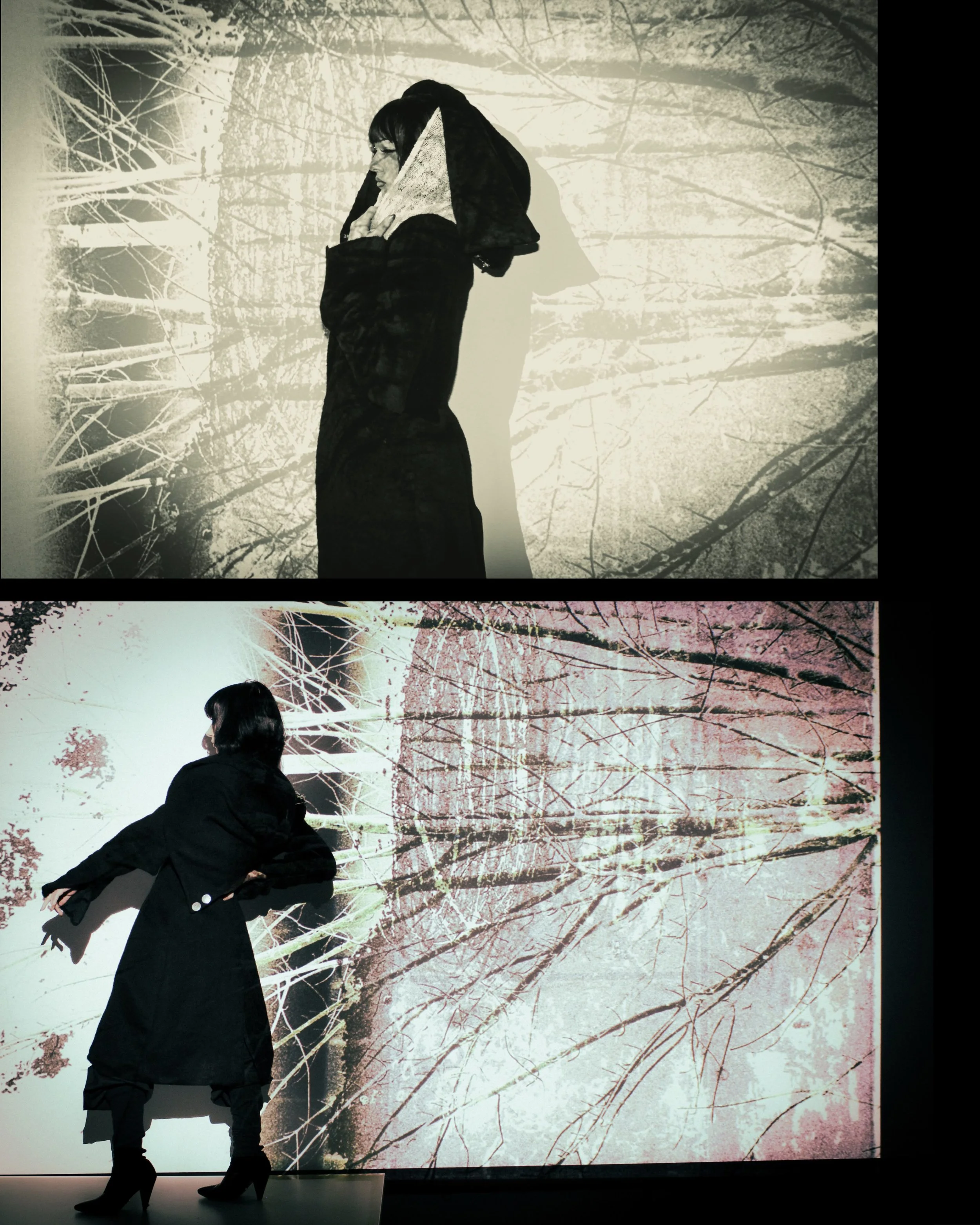

Wade’s guiding principle is honesty over performance. In an industry that often rewards attention more than intention, she defines success as creating work rooted in integrity, work that reflects her values rather than what is trending. India’s craft traditions shape the foundation of her perspective. She is keenly aware of how many artisans are being pulled away from their heritage to meet the demands of fast fashion, and she is committed to preserving traditional materials by reimagining them for contemporary use.

Her silhouettes might look modern, but her materials and methods remain grounded in craft. Recently, she has been exploring how technology can coexist with tradition. She has been pairing knitwear programming with Indian silks, experimenting with coded pattern structures, and developing textiles that merge heritage with innovation. To her, these blends of old and new are not contradictions but opportunities to tell deeper and more meaningful stories through design.

As an international student, her challenges were less cultural and more logistical. Restrictions on work and limited opportunities for self-sufficiency made things difficult, but she eventually found a sense of belonging through two communities: her creative peers at Westphal and a circle of international students who shared the experience of navigating distance, identity, and ambition.

Her message to young creatives in Asia is simple. Communicate through what you make. Build evidence through collections, samples, and prototypes so your family can see the things you may struggle to express with words. Looking ahead, she hopes to build her own label, one where storytelling shapes the product and where technology and tradition evolve together, without losing their authenticity.

Asian creatives are often expected to follow a narrow script, yet the stories of Rashidah Salam, Zeba Farida, Preksha Wade, and my own show that there are many other ways to define success. Our paths may look different, shaped by culture, family, and opportunity, but each of us chose creativity knowing it would challenge expectations. That choice is at the heart of this piece. For every young Asian or South Asian creative standing at a crossroads, wondering whether it is worth pursuing the thing that lights you up, this is your reminder that there is no single correct path. You can write your own script, carry your culture with you, and still build a future that feels like yours. Creativity is not a detour. For many of us, it is the destination.