Before It Was a Trend

Across global runways and social media feeds, echoes of South Asian dress appear in the art of draping, intricate embroidery, and wrap silhouettes — a testament to a textile heritage shaped by centuries of craftsmanship and cultural meaning. Global reinterpretation has given these traditions new visibility, but it has also exposed ongoing tensions around ownership, recognition, and the difference between honoring a culture and repackaging it.

These styles did not suddenly emerge from Western fashion cycles. They originate from long-established systems of clothing, technique, and symbolism across South Asia. These elements have been adapted, renamed, and absorbed into Western markets, often without acknowledgment of their origins. Looking more closely at where these aesthetics come from invites larger questions about how fashion ideas travel, who receives credit, and how cultural influence is transformed into a commercial trend.

In recent years, this translation has become especially visible. The “Scandinavian scarf” controversy in 2023 drew attention when European influencers promoted a blouse, skirt, and long draped scarf as part of Nordic minimalism, despite their resemblance to lehenga and dupatta silhouettes. Brands such as Reformation have released coordinated scarf sets and embroidered low-rise skirts styled as Y2K revival pieces. At the same time, retailers like Mango and H&M have marketed asymmetrical dresses with embellished fringes that echo South Asian draping and surface techniques. At the fast fashion level, retailers such as Princess Polly, Edikted, and Shein regularly sell heavily embroidered camisoles, beaded two-piece sets, and scarf-top silhouettes. These pieces often mirror South Asian embroidery and draping traditions, yet their cultural origins go unnamed. What was once shaped by regional craftsmanship and generational skill is commodified as a seasonal aesthetic.

Four recurring elements stand out: draped scarves, wrap silhouettes, intricate embroidery, and layered gold jewelry. Each appears repeatedly in Western fashion. Each carries a longer history.

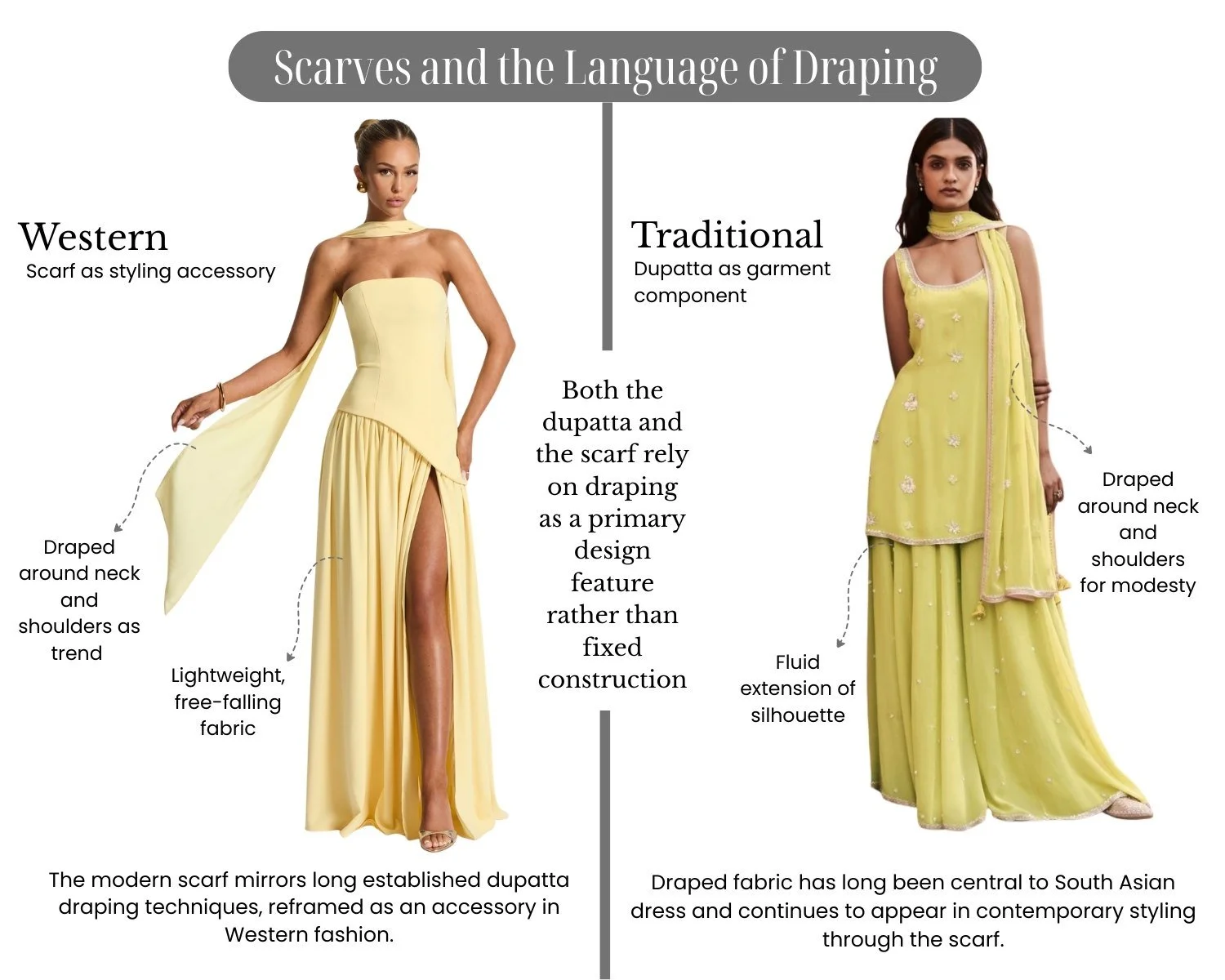

Scarves and the Art of Draping

Scarves have become a visible styling trend, embraced by celebrities such as Hailey Bieber and Bella Hadid. In 2025, Reformation’s collaboration with Devon Carlson featured coordinated low-rise skirts and matching scarves. Around the same time, Mango released an asymmetrical scarf dress. On TikTok, creators have promoted the “Scandi scarf,” framing draped blouse-and-skirt sets as minimalist European design.

In South Asian dress, however, draped fabric carries contextual meaning. A dupatta pulled across the chest can signal modesty; placed over the head, it may reflect respect; worn loosely at a wedding, it suggests celebration. Often, it is adjusted instinctively by a mother or grandmother before stepping outside — a gesture rooted in tradition rather than trend.

When the silhouette reappears in Western fashion, the form remains while its cultural context recedes. What circulates is the aesthetic, not the lineage behind it.

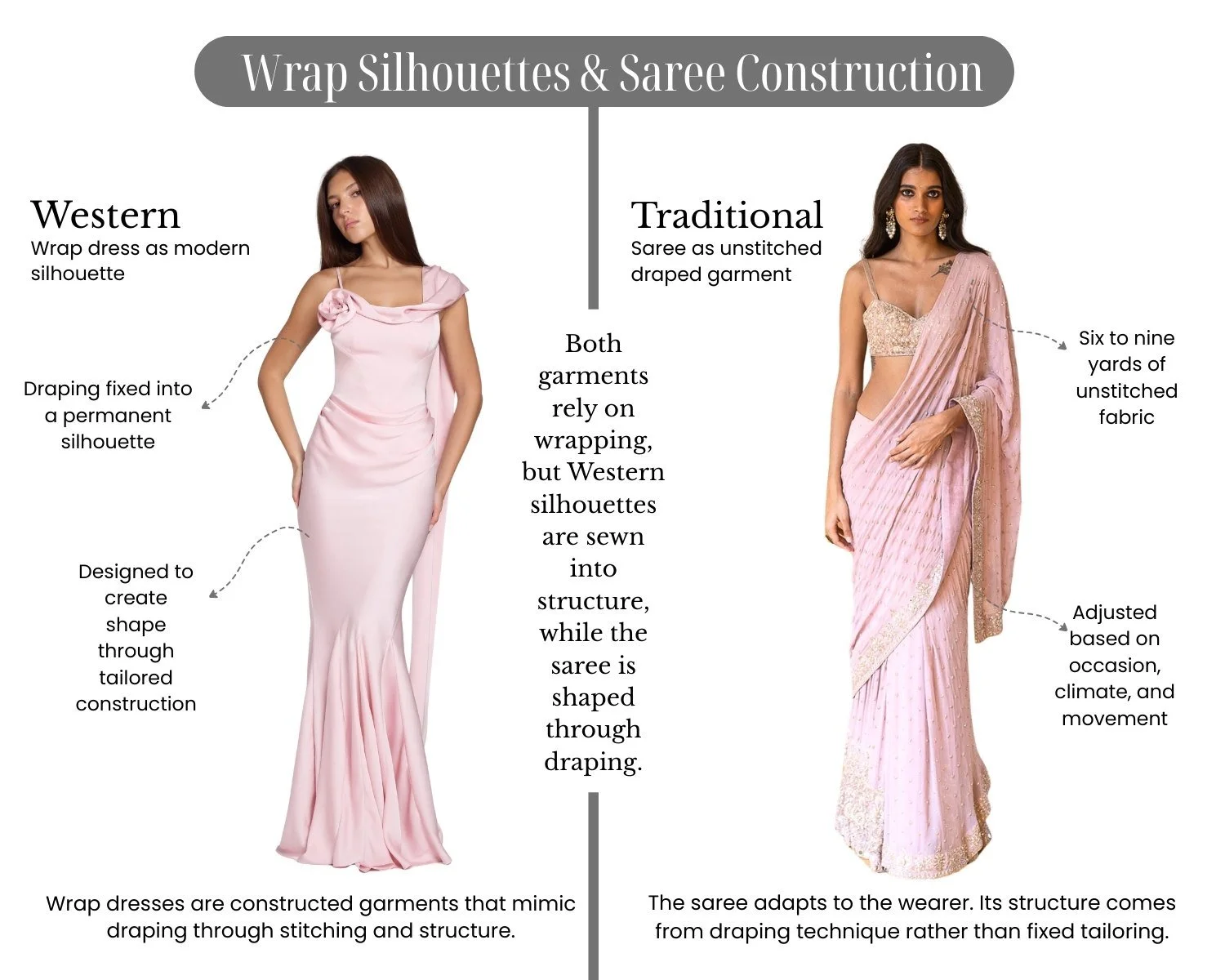

Wrap Silhouettes and Saree Construction

Wrap dresses are often praised as flattering and innovative and are traced back to Diane von Furstenberg’s 1970s designs. Yet the concept of wrapping fabric around the body as the foundation of a garment predates modern fashion by centuries.

The saree, referenced in ancient Sanskrit texts and documented in early South Asian civilizations, relies entirely on draping rather than fixed seams. A single length of cloth can be pleated and wrapped in dozens of regional styles, adapting to climate, labor, and occasion. Fluidity is not merely aesthetic; it allows freedom of movement and wearer agency. Garments such as the veshti and dhoti follow similar principles of wrapping rather than tailoring.

Contemporary designers such as Jacquemus and Zimmermann continue to promote wrap silhouettes as effortless and liberating. Yet what is framed as modern innovation mirrors a long-standing design philosophy rooted in adaptability and movement.

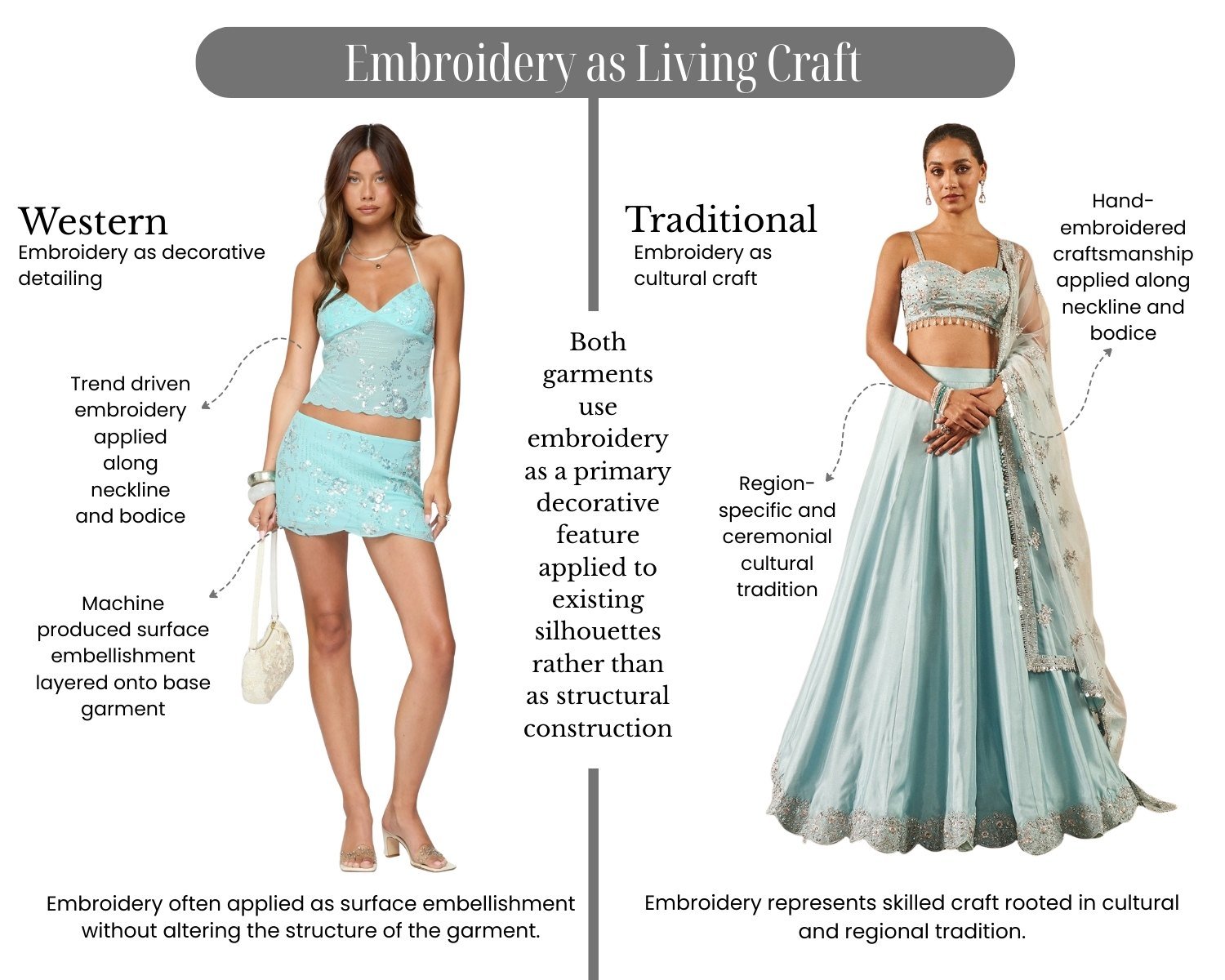

Embroidery as Craft, Not Just Detail

On Western runways, embellishment is often described as ornate or “festival-inspired”. Sequins and metallic threadwork appear in resort collections and fast fashion alike. In South Asia, embroidery traditions such as zardozi, mirror work, and chikankari are regionally specific craft practices passed down through generations. Varanasi silk woven with gold and silver brocade carries ceremonial and historical significance. These techniques are not simply decorative; they are embedded in community and heritage.

Yet retailers such as Princess Polly, Edikted, and Shein frequently sell embroidered or beaded tops labeled as “Ibiza style” or “sequin tops,” flattening complex craft traditions into seasonal trend language. The visual appeal remains. The cultural context does not.

Layering Jewelry and Everyday Meaning

Layered gold jewelry has become a statement styling choice in recent years. Multiple chains are stacked over simple tops, bangles are worn in clusters, and rings are layered for visual impact. On red carpets and across Instagram, this look is framed as curated maximalism or effortless layering.

In many South Asian households, however, layering gold has more depth. It is a long-standing cultural practice. Jewelry is given as gifts at milestones such as weddings, births, and religious ceremonies. Pieces are accumulated over time and worn daily, serving as both adornment and a form of financial security. The layering reflects continuity — a visible record of memory, inheritance, and family history.

As this practice enters Western fashion, the industry adopts only the visual effect of stacking. What is absent is the intergenerational meaning behind it. The difference is not the gold itself, but what the layering represents.

Recognition, Not Reinvention

None of these suggests that cultural exchange should be restricted. Fashion thrives on influence. The difference lies in recognition. As consumers, particularly younger generations, grow more curious about where their clothes come from, it becomes worth considering fashion not as a cycle of constant reinvention but as a continuum of influence. Recognizing origins does not limit creativity. It gives it depth.